Meet CJ Jeffers of Jeffers Event Services or JES, a fictional character from a fictional company that might look a lot like companies you know. CJ and his management team are featured in my latest book, “Balance: How to Build a Scalable Business With Less Stress and More Profit.”

CJ started the company in 2001 and focused on production agencies who needed boutique services. He’s a classic owner-operator who I met briefly a few times over the years. As we approached the end of my background review of the business, CJ texted me just after I arrived in town to meet his team.

“Give me a call when you get checked in. Change of plans for tomorrow morning.”

Meet the Banker-in-Law

CJ had one last detail, and I could tell he’d been dreading it. I needed to talk to his father-in-law, Robert Chesterman of Chesterman Bank and Trust.

Robert had loaned CJ the capital to start the business in 2001 despite the ongoing recession. CJ was nervous about Robert and sensitive that his wife was caught in the middle. It was also clear that he resented the fact that Robert held sway over him by being his 25% finance partner.

I arrived early for my appointment with Robert at the bank’s main branch. This wasn’t a big downtown skyscraper business — Chesterman was a regional bank, privately-owned, and occupied what I suspect was a building they once repossessed and remodeled.

Early was the right choice. At exactly one minute before our appointment, Robert’s assistant swooped into the lobby and escorted me to a conference room. Robert entered from a door inside the conference room, which was clearly connected to his office. He quickly delivered a firm handshake, he thanked me for coming to him (like I had any choice), then he sat down and went straight to the point.

“I don’t know why CJ doesn’t make more money. It doesn’t make sense. The ups and downs — that’s what they need to fix. It seems like they need more salespeople. Is that where you’re focused?”

There was a time that someone like Robert would have intimidated the heck out of me, but I’ve had this conversation before. I find that folks who know a lot about big business don’t always understand how small businesses work. Robert had grown his company from scratch, so he knew both sides. Clearly, he felt there must be some sort of shortcoming in CJ that would explain it all.

“There are 20,000 companies like CJ’s in North America, and 80% of them would envy his profitability. But you say it’s nothing to write home about. 99% of those companies haven’t figured out how to solve the seasonality of this industry either. However, that seasonality points us to a better model for managing these businesses. This is where I’m focused.”

Robert leaned back a little to indicate he was willing to listen.

“What CJ needs to do is turn down more work. His company is built to take on as much work as they can in the 4-5 months that have reliable demand. Those months can look pretty good, especially if the projects don’t overlap too much. But that leaves 4-5 months of break-even revenue and two months of huge losses.”

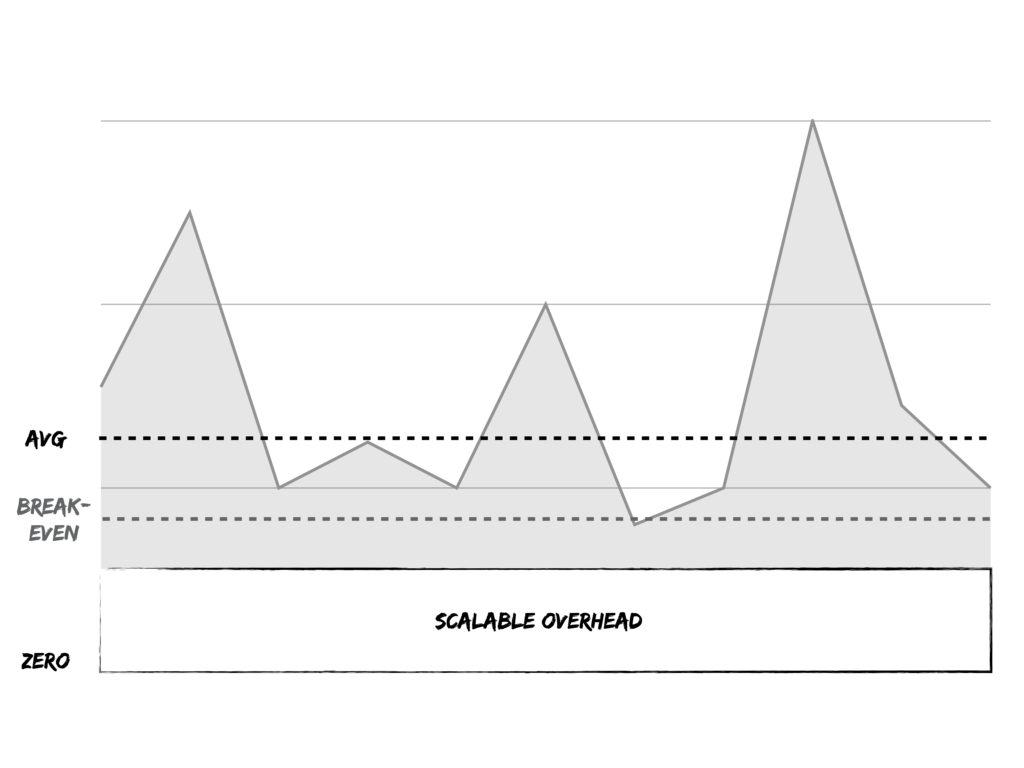

Robert seemed engaged. “CJ said something about being more scalable. When the last recession started, his revenue dropped and he wouldn’t lay off any workers. He said he needed them for the busy months to keep job cost down.”

“That’s what a lot of folks thought, but that’s the opposite of scalable. A scalable business wouldn’t retain all the direct labor CJ has on his payroll. They’d outsource during high demand and even in low demand. As revenue increases, net profit as a percentage of revenue should increase.”

“How does turning down revenue even make sense?” Robert was deciding whether I was a crackpot or a mystic, but he was hanging in there with me… so far.

I explained that there was a practical limit to what these companies can handle in a busy period. The timing of projects — the overlap of the live audience shows — also affects how much they can do. However, turning away business is terrifying.

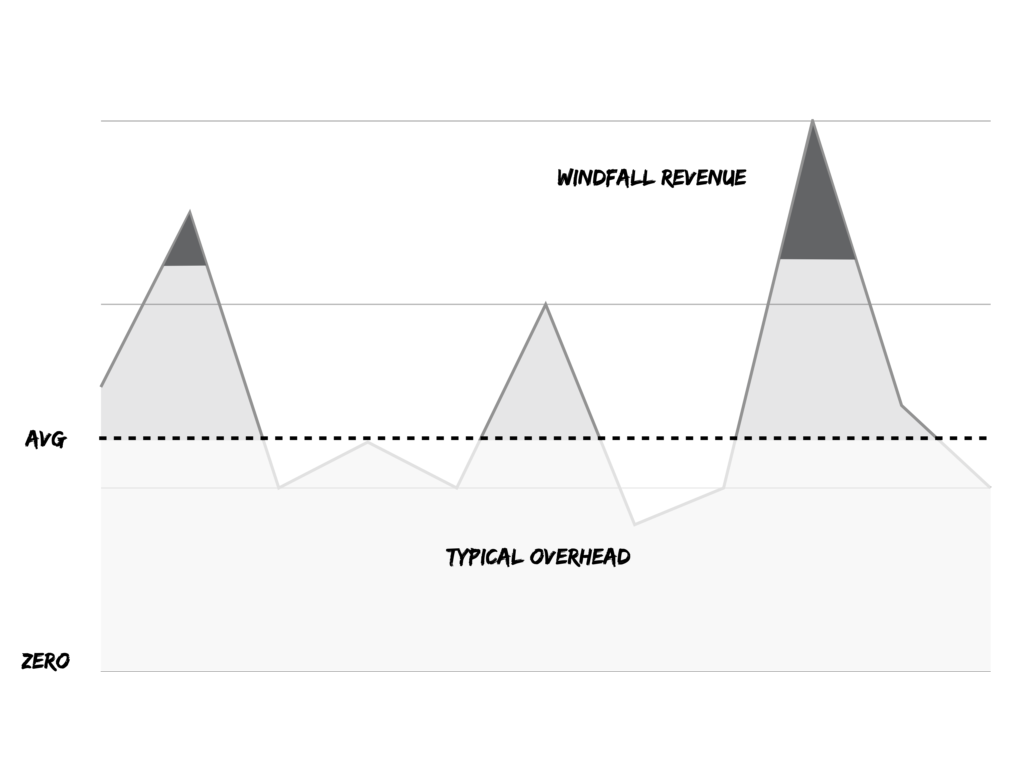

If we analyze those peak periods, we see a point where the effective utilization of the internal resources hits its peak. After that point, the blended gross profit of all the projects starts to shrink. It’s still gross profit, but the risk increases. Now, take out the one job — it’s almost always one project — that tipped that company over capacity. That’s the windfall project they took on that they shouldn’t have.

By knocking off the self-inflicted spikes in revenue and focusing on how to make the company profitable every month, we actually solve the formula for making windfall projects more profitable. 80% of CJ’s team is designed to be direct labor, but there are only enough billable hours to cover half of that.

“This is about outsourcing more,” Robert intoned flatly. He wasn’t impressed.

“It’s impossible to manage a seasonal business — especially in Live Events — without outsourcing. What CJ and his team need to learn is how to sell and plan a job that can be reliably outsourced. It starts with putting together a solution, then pricing correctly, then managing a scope of work, and finally communicating it with the team that will execute.”

“I help them set up their job cost system. They can forecast and track profitability and account for overhead. It’s really foolproof.”

Job cost is the battleground for these conversations. I was hoping he would bring this up, so I didn’t have to. I explained that the mechanics of the job cost spreadsheet worked fine, but it was the assumptions that got CJ into trouble. Robert probably got the assumptions from CJ, then added the overhead allocation piece, which is what you would do in other industries.

“Like most job costing systems, it also rewards the use of inside resources like people and equipment by assigning them a lower cost basis. This in turn allows the selling team to discount more to the customer if they need to win the job. The first job sold looks wildly profitable, while the last one sold looks awful.”

“I get it.” He was tracking me now. “That’s why the windfall jobs, as you call them, are so important. The gross profit is lower, but the sheer scale makes that month look more profitable.”

“Exactly.”

“What needs to change?”

I explained that designing a company that uses less overhead more wisely was key. While I didn’t have the full picture yet of what JES needed, I shared what I knew would be critical for this company.

- Always sell from replacement cost. Add margin commensurate with the inherent risk of the product or service. Every job will be inherently profitable, no matter how busy you become.

- Staff your business with experts in sales acquisition, project planning, and supply chain management. Outsource everything else. If the team isn’t trying to micromanage resources to keep costs down, they have a lot more time to double your business volume.

- Be laser-focused on what types of customers you want to work with. There’s plenty of work out there, so you can afford to be pickier.

- Turn down work when your suppliers can no longer keep up.

“The devil is in the details,” he smirked.

Leave a Reply