Listen instead on your Monday Morning Drive:

Words matter. So do numbers. Especially the numbers in your financial statements.

When owners hire me, they always have questions. “Do I need to hire more people?” “Should I buy my own building?”

My answer is always the same: “I don’t know. Let’s look at your numbers.”

The Phone That Never Rang

Years ago, a company reached out to my firm about an acquisition. Our principals spent three and a half hours in their office, discussing whether we’d be a good fit. On the way out, one principal turned to his partner and asked what he had noticed during the meeting.

“The phone never rang,” the partner said.

Think about that. Three and a half hours without a single interruption. What does that say about a business?

We can’t extrapolate one observation into a complete picture, but intuition often tells us whether we want to ask more questions.

From One Week to Two Hours

When I started consulting 20 years ago, analyzing a new client’s financials took me a week. I’d pore over everything, trying to understand which numbers went where.

Every question required digging to find the answer, partially because I lacked experience and partially because no two companies kept their books the same way.

After many years of practice, the numbers started telling me what questions to ask. Today, 75% of my analysis happens in two hours or less. From those financials, I learn about how the business works, how the team thinks, and even the company culture.

Financial statements aren’t exciting. But they are revealing.

What I Used to Look At

Twenty years ago, I focused on different metrics. Here’s what mattered then:

Revenue to full-time equivalent employees. If the number was low, you might’ve been overstaffed. If it was high, you probably needed more people. Companies with high revenue per FTE were often profitable, albeit stressed, because their processes depended on everyone working extremely hard.

Sub-rental as a percentage of revenue. We’re all rental businesses at the end of the day. If you were sub-renting too much, you needed to own more equipment to keep that money in-house.

Total labor as a percentage of revenue. Back then, it was about 30%. We tracked this metric to verify that we had enough people on shows and that we recruited effectively.

Average monthly expense alignment. Were you built to handle the middle six months of your business? You have three slow months, three busy months, and six normal months. If you’re set up for the normal months, you’re understaffed during busy times (requiring more outsourcing) and overstaffed during slow times.

These metrics reflected organizational efficiency. Nothing more.

What I Look at Now

People still ask me about the right revenue to FTE ratio. I have no idea. It’s whatever allows you to do your work profitably.

Experience makes me more efficient at reviewing numbers, but what I’ve learned about building scalable businesses and balance also points to different metrics that matter most.

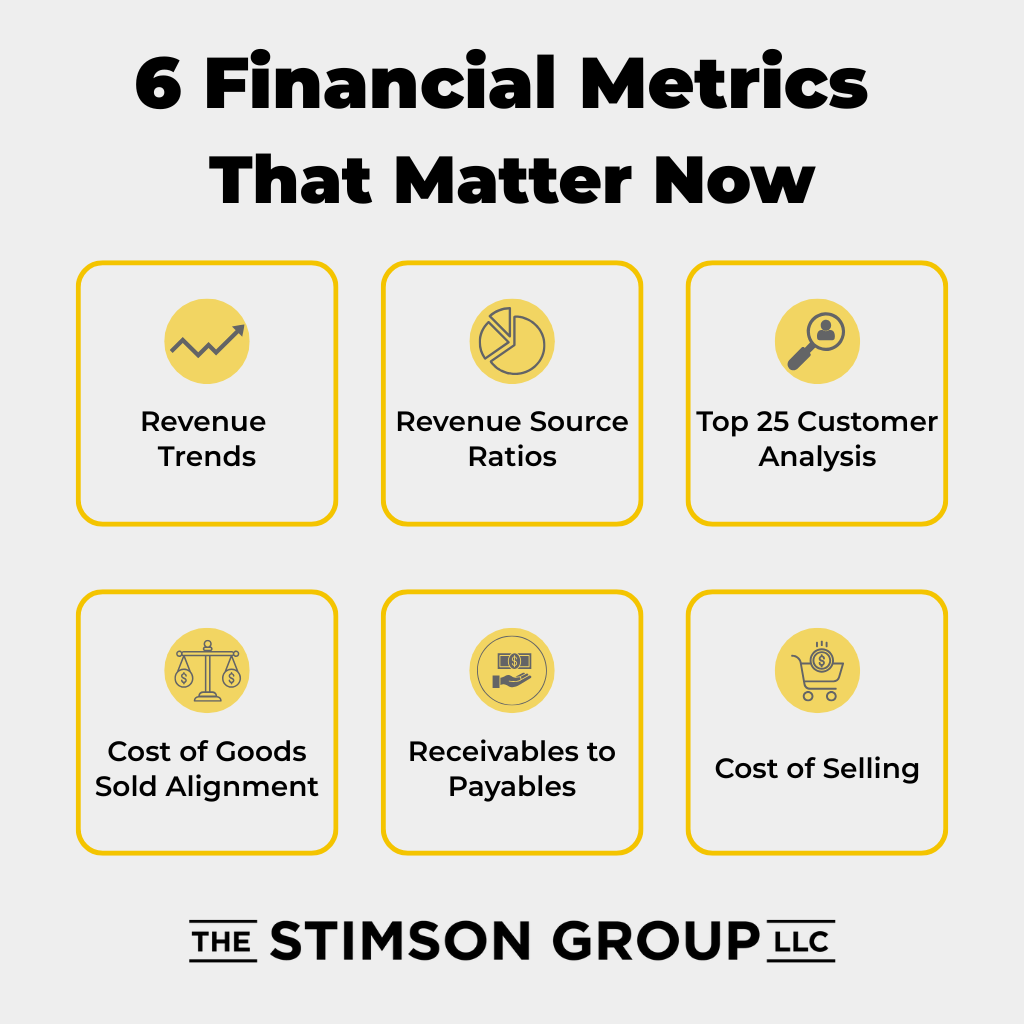

Instead of tweaking every number that’s out of whack, I focus on six big factors.

1. Revenue Trends

I examine monthly revenue and profit over a 36-month period. How seasonal is this business? How often does revenue generate profit? Is revenue growing, flat, or declining relative to the economy?

I back out windfall jobs. They’re not true growth. They subsidize a busy month, but they aren’t the normal course of business.

Companies often feel their revenue is growing. Their revenue is growing, but if it’s not growing as fast as the economy, while expenses are always rising, they’re making less money every year.

What this tells me is: Is this business proactive or reactive to growth?

2. Revenue Source Ratios

I look at the ratio of key revenue sources over time (not single months or single jobs). A trailing 12-month view shows how much you charge for:

- Labor and services

- Owned equipment

- Logistics and other direct costs (travel, trucking)

These ratios tell me plenty about your business.

If equipment revenue exceeds 60% of the total, I expect to find pricing problems. Many companies undercharge for labor and logistics to subsidize their rental gross profit. The numbers show we’re putting value in the wrong place.

When we’re busy doing extremely valuable work, we’re not making as much money as we should.

3. Top 25 Customer Analysis

Understanding who generates 80% of your revenue helps you understand how you manage revenue and what that revenue is worth. This analysis uncovers concentration risk and growth opportunities.

4. Cost of Goods Sold Alignment

For every revenue stream, there’s a direct cost. These need to line up clearly. We can’t muddy the waters by lumping costs together.

If you sell trucking services, you need a line item (or two or three) in cost of goods sold for trucking costs. I need direct comparisons of revenue and the corresponding cost of goods sold.

Most companies don’t have their books set up this way. It’s a crisis. We need to fix this.

5. Receivables to Payables

How quickly does the company get paid? How quickly do they pay? Is there enough cash to always pay suppliers on time?

When owners stress about cash flow, they’re distracted from the issues causing the problem. Poor cash flow is almost always tied to low profitability, which typically comes from underpricing. We can’t fix profitability overnight, but we can make other changes to alleviate cash flow.

6. Cost of Selling

This isn’t cost of goods sold. Cost of Selling is in overhead expenses, the money you spend to earn revenue: marketing, business development, account management, commissions, promotions, sales travel, incentives, proposal development, etc.

What’s a healthy percentage of selling expenses to grow a business? That’s the right question. Most companies don’t post expenses this way, so they’ll never know.

This is critical to your business.

The Real Problem

Many clients’ numbers aren’t set up correctly for this analysis. Revenue streams aren’t properly delineated. People post lump sum revenue because their invoices are lump sum. But where’s the breakdown? How did you get to that number?

Tax accountants or QuickBooks wizards, who don’t understand how your business works, set up your books in a way that makes sense to them. The result is that you can’t see what’s actually happening in your business.

Looking Forward, Not Back

The purpose of management accounting is to predict results. If there’s a soft spot in your revenue, you’ll see it in real time on your forecast. You’ll know when to make adjustments.

More time looking forward leads to more profit. But first, we have to put the numbers in the right place.

Your numbers don’t lie. They tell a story about your business, processes, and culture. Are you listening to what they’re saying?

Leave a Reply