Listen instead on your Monday Morning Drive:

You know Bob. Every live event company does.

Bob’s been a producer for years. His clients love him. He’s charming, creative, and a beast on a show site. He says all the right words: “You’re so important to the process. I can’t do a show without you.”

You sit down with Bob and hammer out a fair budget. The proposal doesn’t include many frills. And yes, you remember last time when Bob said he’d make it up to you on the next job. Well, this isn’t that job either. He’ll take care of you later.

The project starts. Bob meets deadlines. The deposit check arrives, but there’s a hiccup at the bank. Don’t worry, he says.

Then, Bob starts adding meetings. The client wants one more video, he says. The budget will come later.

Then, Captain Chaos shows up.

Suddenly, you receive freak-out calls. Bob says the client is being difficult and wants to change the lighting design. That item you don’t remember talking about was included, right? Well, it should’ve been.

You throw people at the problem to make it work. Bob knows he won’t pay for it because he didn’t agree to it.

The show happens. The client is happy. Then Bob tells you where you screwed up and asks for money back.

But Bob is loyal. He’ll be back with another show.

The Real Problem Isn’t Bob

We all have chaotic clients. But are they actually chaotic, or are they just better at controlling the narrative than you are?

Some clients are unscrupulous. Most clients are just better control freaks than we are.

Nobody else wants to work with Bob, so he’ll hire you again. You have nothing to lose by taking control.

Not every Bob is manipulative. Some clients are chaotic because they’re insecure or panicking. To help them, maintain control of the project through its ups and downs.

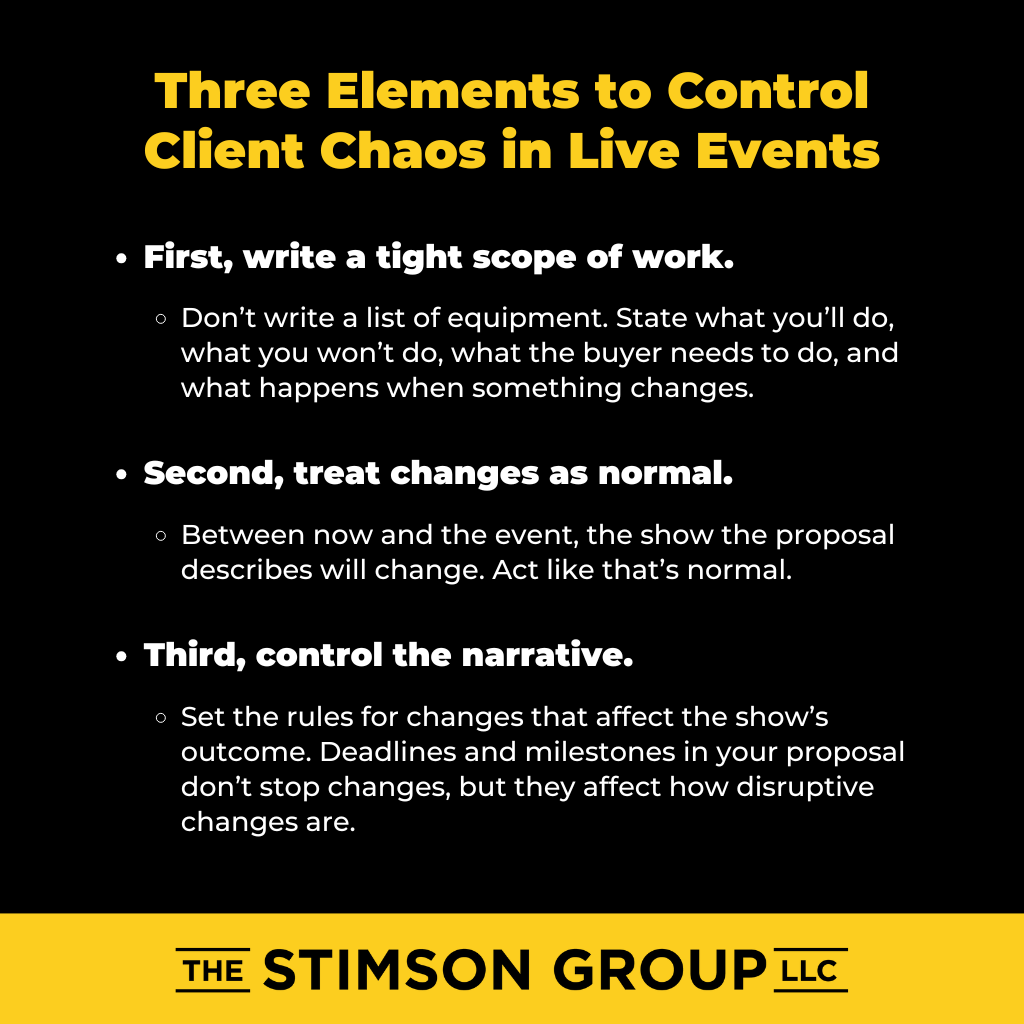

Three Elements You Need to Change

First, write a tight scope of work. Don’t write a list of equipment. State what you’ll do, what you won’t do, what the buyer needs to do, and what happens when something changes.

If your client or team veers off scope, tap the brakes. Stop the work if you need to. Figure out the issue. Your scope should say, “If we’re off the path, we take corrective action.”

Second, treat changes as normal. Between now and the event, the show the proposal describes will change. Act like that’s normal. Don’t let your operations team get upset every time you add a screen, take it out, add it back, and take it out again.

Third, control the narrative. Set the rules for changes that affect the show’s outcome. Deadlines and milestones in your proposal don’t stop changes, but they affect how disruptive changes are.

How to Control the Narrative

Be ready to stop work when chaos presents itself and you receive conflicting information.

You might insist on a meeting by saying, “I need to talk with you by the end of the day. I’m putting these items on hold until we talk. We’re pushing back the deadline for client review of content at least 24 hours after I talk to you.”

This way, you control the narrative, and the ball is in your client’s court.

If criteria aren’t being met — if you didn’t get deliverables, content pieces, logos, revisions, or client approval — stop work.

When you miss a deadline because of a change or reset the deadline, move deliverables forward. Look at how that affects the entire schedule on paper.

Make sure the customer understands how integrated your process is. Five people on your team are in the middle of work this change will affect.

Repeat this mantra: “I have to stop work because I can’t have five people moving in the wrong direction at the same time.”

Break Projects Into Sub-Projects

When live event companies move from a rental mindset to a project mindset, they often treat all work as one big project. This is a mistake.

Deliverables have to happen. These deliverables are sub-projects that allow other sub-projects to start.

For instance, if you don’t finish creative and technical concept design, you can’t write a project scope, create a budget, or draft a timeline. Concept design is valuable, but you won’t get a project scope, budget, or timeline until it’s complete.

Production design comes after concept approval. You move from napkin drawings to technical drawings. From renderings to fabrication.

Review Points Are Control Points

When you start a new phase or sub-project, conduct a timeline review. Update the timeline based on what changed since you last looked at it.

Do a cue-to-cue on the show. Walk through each element to make sure you’re addressing all the details. This way, you catch mistakes, keep everybody on track, and manage expectations.

You only have to hit the highlights: “We have an intro for the CEO. We roll the video. The CEO walks on stage. Keynote presentation. The CEO recognizes somebody in the audience. We break for lunch.”

After the cue-to-cue, conduct a budget review. Every time you update your timeline and do a cue-to-cue, you’ll find items that might affect the budget.

These are your control points with the customer. You can add them whenever you need to in the timeline as places to stop, check, and regroup.

Technical Planning Updates Everything

As design, fabrication, and implementation occur, so does technical planning, which affects the timeline.

You design the lighting system you’ll send, the audio system design, the video system design, where people sit in the room, where the control deck goes, etc. This updates the timeline for prepping the order, getting it to the job site, loading it in, and being rehearsal-ready.

Update that timeline. Sit down with the client and do a cue-to-cue based on technical elements. Did any of the discussion change the budget? Complete a budget review.

You might say, “We didn’t like how this transition was going to work, so we’re adding this element. Adding it will increase this cost. We’re reducing another cost here, but there’s a budget change.”

Clear communication means you control the narrative.

On-Site Control

When you load the show, your production team needs to sit down with the client at a reasonable time before rehearsals begin.

Update the timeline. Walk through the cue-to-cue again.

“The speaker won’t make it; we have this speaker instead” changes the cue-to-cue. “Does it affect the budget? No? Good. We’re on the same page.”

On site, a budget review means change orders. “We need two more downstage monitors. The addition will cost about $2,000 as a change order.”

When the job is over, schedule another budget review: “Here’s the budget when you left the shop. Here are the change orders from on site. Here are the final numbers.”

Your scope of work defines these checkpoints so you can get the work done.

Build Better Budgets

Once you understand how the project process works, your budget changes.

For every element of the show, have a baseline budget — the minimum required that can’t be reduced.

Enhancements are variable. You can add more or fewer. Make it clear in the scope what qualifies as an enhancement and what qualifies as a baseline.

Your budget always includes a schedule. How do you set the timeline? How do you define the cue-to-cue process and the change order process in your original budget?

This budget exists under certain conditions, following a certain process.

Project Sales Changes Everything

For each project or sub-project, you can have a scope of work, deadlines, and next steps. Then you create a summary for each sub-project and a summary for the entire project that shows how each sub-project fits into the budget.

This process is different from thinking like a rental company since it gives you the power to make sure the show goes well.

Bob will always be Bob. But when you control the narrative, Bob becomes just another client with a process to follow.

Leave a Reply