Listen instead on your Monday Morning Drive:

Proposals should be routine in your business. You write them all the time because customers don’t buy AV services over the phone. They need documentation.

The problem? Most proposals are terrible.

I see too many 35-page documents full of pointless information, pictures that have nothing to do with the show, pages of marketing materials irrelevant to the actual project, unclear scope, and options everywhere. The result is that money gets left on the table.

There’s a disconnect between client expectations and your deliverables. If you don’t address expectations in the proposal, deliverables lack context. Every reader interprets your proposal differently, and chaos ensues when you’re selling to a committee.

Why Buyers Want Proposals

Buyers need proposals for specific reasons. Understanding these reasons helps you write better proposals:

- They need to compare vendors, which is exactly what you’d do in their position, so they need to see quotes side by side.

- They need a checklist. As you do the work, they can verify you’re delivering what you promised.

- They need to share information with stakeholders. Your proposal captures all your conversations, discovery meetings, and design talks on paper so they can share it with others.

- They’re educating themselves about cost. Most educated buyers use proposals to learn what services actually cost.

- They don’t know what to do next. A proposal seems like the logical step.

When a consulting prospect says, “Send me a proposal,” I often say no.

Instead, I say, “First, we need to make sure we understand what we’re talking about. I’ll tell you what it costs within a range, and we can see if this is worth writing a proposal about.”

That’s just my preference. I like to write agreements, not proposals. But sometimes, you have to go through the proposal step first.

What Proposals Should Do

A good proposal performs clear jobs:

- Restate the client’s request in terms of products and services. They’re asking for outcomes, so use their language.

- Present the price. Get it out of the way.

- Document the remaining options or decision points. Include what’s in and what’s out. Define who’s responsible for what.

- Trigger the confirmation process. Next steps matter. Don’t ask people to sign too soon. I’m not rushing to the last page of a huge document to sign it. That’s counterintuitive.

- Launch the project. With a signature, you launch the work. Maybe it’s the full project, or maybe it’s just the next step.

When Proposals Work Too Hard

Some proposals try to accomplish too much.

Don’t create the ask on the buyer’s behalf for the first time in the proposal. Clarify that in the discovery process. Present your understanding of their ask before you write the proposal, and get confirmation that you’ve got it right.

Don’t ask buyers to review details to see if you made mistakes. They don’t know your job. How would they know if a cable or technician is missing?

Don’t introduce non-intuitive options. The buyer will reject your offer because an option doesn’t fit. They’ll feel misunderstood and start over.

Don’t list every detail of every day of every item. Your proposal isn’t your pull sheet. You’re in a service business. Show them the services you’re providing with an end result.

The Phases Before You Write

You need conceptual agreement before you write a proposal:

- Discovery. Learn about each other.

- Ideation. Reflect ideas and design back and forth to get a clear picture.

- Develop pricing. Build your cost budget and pricing strategy away from the customer. Float it past the buyer before you put it in the proposal.

- Present. Restate the solutions. Layer in the value. Present the proposal whenever you can.

- Close. Agree to move forward on at least one element.

Think about the phases. Are you trying to sell every step of a nine-month process for a show that hasn’t been clearly defined yet? Maybe selling the first step makes more sense than selling the fifth step.

Get the conceptual agreement first. “If I can write a budget that meets your criteria, addresses your ask, and comes in under your $35,000 budget, is this what you want to see?” Get that “Yes.”

Then, ask about their decision criteria. “What’s your process? When will you decide? What’s your final decision criteria?”

Remember, you’re part of somebody else’s buying process. You need to understand what that process looks like.

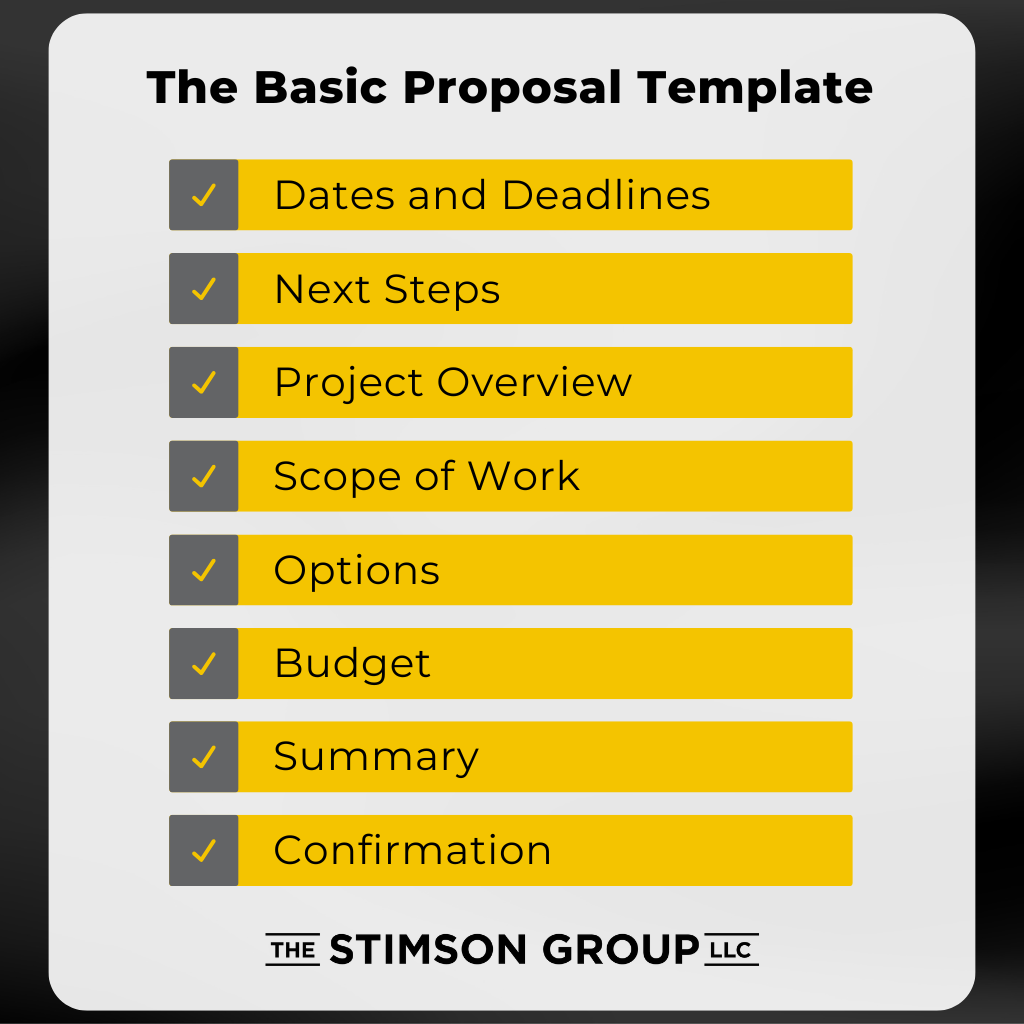

The Basic Proposal Template

Here’s what goes in a straightforward proposal. For bigger projects, duplicate this template. Each section can be a sign-off point to get the project started while other pieces develop.

Dates and Deadlines

Start with when the proposal was prepared and delivered. State the offer’s expiration date, unless otherwise noted.

This step is about the proposal, not the project.

Next Steps

Tell the buyer what to do. Be very clear.

E.g., “Review the scope of work, descriptions, deliverables, and budget as soon as possible. If you have questions, requests, or modifications, submit them at least 24 hours before the proposal’s expiration date. I’ll be happy to revise it. If this proposal meets your needs and expectations, follow the instructions under Confirmation.”

Project Overview

Describe the ask in the customer’s terms in one paragraph under 150 words. “The client is gathering these people for this purpose on these dates in this location.”

They already know this, so show them that you know it. When they share the proposal with their team, everyone will know you understand what they’re asking for. If there’s a miscommunication on their end, they’ll spot it immediately.

Scope of Work

Describe what you’re providing and the work you’ll perform in the customer’s terms. Include specific deadlines or delivery dates where applicable.

This is where you put inclusions and exclusions. As you think through the scope, clarify what the client is responsible for and what you’re responsible for. Then, note what specifically is not included — and is therefore the buyer’s responsibility.

E.g. “The buyer will provide catering for the event crew per the schedule.” “Seller will arrange and pay for all air travel and accommodate all changes for the show crew.”

Bullet points work great here. Use the fewest words needed to convey the idea.

Options

If there are options, these become miniature scope-of-work descriptions. They follow the same format but are additions to the main scope.

Your main scope includes all the pieces that go together and aren’t negotiable (e.g., “Audio, video, lighting for an audience of X”). These pieces have to be taken together.

Options or enhancements are elements you can add or delete (e.g., recording, post-event highlight reel, etc.).

Budget

Summarize the budget. The only details your customer needs are about price and quantity, which the customer can freely alter.

If you’re giving them access to every detail, like the number of wireless mics, show them what happens if they revise it. Better yet, write “up to 10 wireless mics” and move on.

I’m a one-price person. Some of you want to show equipment price, labor price, and logistics price. Consider your audience and make the best choice for them.

Your goal is to say, “Here’s one price for all we discussed,” and work from that number.

Summary

List the title of each major scope-of-work element or deliverable. Integrated elements should be listed as one item. For example:

“Baseline package: $50,000. Recording option: $5,000. Post-event video: $3,500.”

Confirmation

Show the buyer how to confirm. A link to a secure document they can sign and that takes them to the payment page works well. Make sure that link expires when the proposal expires so they can’t take advantage of you.

Present It Live

Present this live in person or by Zoom if possible. You’ll have much better results.

Someone will actually read this because it reads the way a buyer thinks rather than the way you want them to think. That gets buyers to pay attention to your proposal.

Leave a Reply